A friend of mine always used to say that a poem is never really finished. From what I’ve learned from workshop, it seems apparent that there’s no way to please everyone with every word choice and punctuation mark, but that doesn’t stop me from trying in the revision process. So what about you? When do you know you have a satisfying enough product that you cease working on it?

There are different layers to this question, I think, because I think there’s a certain level of “done” that I get to before I show a poem to anyone else. Then once I get feedback, however, I often get stuck. It’s honestly usually more helpful to get feedback from only one or three people, since the heavy influx of advice we get in workshop always has me wanting to split a single poem in about a dozen different directions.

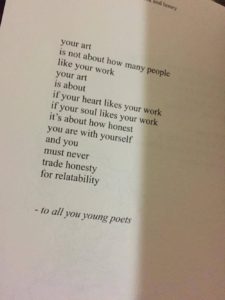

I feel like this post is getting a little scattered, so my main concern is this: I’m looking to submit my poetry to some different lit mags pretty soon, but I need to figure out when my poems will feel accomplished enough to take that step. Maybe they’ll never feel like they’re completely done, exactly, but maybe I’ll be able to get them to a place where I’m satisfied with where I’ve gotten them. Does anyone know what it takes to bring a poem to a satisfactory level of completeness?