I returned from the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) conference in LA a few weeks ago, but I haven’t had much time to set down my thoughts about it until now. I’m planning on posting my thoughts in a few parts: the first (this one) will be on a panel on poetry, the second will be on two panels on writing and place, and the third will be some brief thoughts on AWP as a whole.

AWP was held in the Los Angeles Convention Center, in Downtown LA. The Convention Center is huge, as Oliver mentioned, about the size and feel of an airport, except with more writers running between the small conference rooms, and a massive book fair in a warehouse-type room in the center of the building. In total we attended seven hour-and-fifteen-minute-long panels. During the panels, writers would sit at a table in the front of the room, present their talks on the topic at hand, and then take questions at the end. I took notes as best I could, so I could bring back this information and share it, and these blog posts are adapted from those notes.

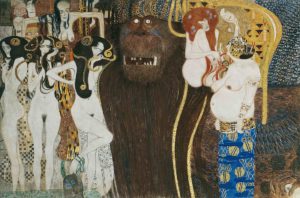

I first attended a panel called: “Poets on Craft: The Furious Burning Duende.” The discussion surrounded the malign spirit that Spanish poet Fredrico García Lorca named the duende in his 1933 lecture “Theory and Play of the Duende.” Essentially, to Lorca, the duende is the spirit of poetry itself, a spirit that rests deep in the heart of the poet. In the lecture, he says, “…the duende is a force not a labour, a struggle not a thought. I heard an old maestro of the guitar say: ‘The duende is not in the throat: the duende surges up, inside, from the soles of the feet.’”

According to panelist Mahogany Brown (a poet, musician and journalist, and a contributor to the BreakBeat Poets anthology), the duende is a spirit summoned from within by fighting death or fighting battles that can never be finished, like racism and oppression. Jaqueline Jones LaMon (a prolific poet and president of the Cave Canem foundation for black poetry), citing Lorca’s lecture, said that the duende “serenades death’s house.” She continued, citing a Luther Vandross interview where he was asked why he orchestrated his live performances in great detail, and he responded that it was preparing (paraphrasing) “for the initial moment when the arena goes black and silent…we as the audience hold our breath and gasp because our breath, our very connection to life–has been taken away.” She concluded that the duende arises from the silences between death and life, and it’s what makes us write. She then read the poem “Far Memory” from Lucille Clifton’s The Book of Light, and her own poem “The Present Song of Seagulls on the San Francisco Bay” to illustrate this principle of poetry arising from the spaces and silences between life and death.

Patrick Rosal (a poet, author of My American Kundiman and many other collections) was the next panelist to speak. He opened with Robert Hayden’s poem “Frederick Douglass”, as evidence for the fact that the duende as inspiration arises from a place between life and death. He also reminded us that Lorca’s project was nationalist, and that his use of the duende was nationalistic, appropriated from gypsies. Nevertheless, he derived lessons from the idea of the duende, and showed us by reading a non-fiction piece he wrote about his uncle, who was poor and worked in a plastics factory in the Philippines, and sang beautiful sorrowful songs. The duende, to Rosal, is the location of deep sorrow within the body, a sorrow he felt in mourning death in his family as well–a sorrow he did not need nationalism to feel. The last speaker, Sandra Beasley, (a poet and a professor at the University of Tampa MFA program), read Sandra Cisneros’s “Night Madness Poem”, which she said claimed duende as a force. Beasley turned our attention to the fact that the duende can also manifest in a poet’s language, with spontaneous verb tenses or multiple expanding metaphors. She then turned our attention to spaces that can hold death, and used the example of a household with family in the military as a place that exists in the “unresolved narrative of death.”

I wanted to spend time outlining this conversation because I think the idea of the duende is something to be aware of while writing. I’ve noticed that this class writes a lot about death, so maybe we’re all already aware of this force, but I think keeping the duende in mind, either as a material product of the writer fighting for life, or as a spirit that lurks within the writer, can help inform all the creative writing you do. Recently while writing and revising I’ve been asking myself if or how my poetry confronts death or inhabits the liminal spaces between life and death, and I think it has been helping me clarify my poetry’s stakes. The idea of the duende has also prompted me to ask myself what my stakes are, where my writing comes from in the first place, and what it might be helping me to fight for. What do you think about the duende? Can you see it in your own writing?

“Municipal Gum” deals with the out of place-ness of a gum tree in the middle of an urban environment, and that same dislocation in the poem’s speaker, who links themselves to the tree by calling the two of them “us” and addressing it as a “fellow citizen,” and that feeling is heightened significantly by the irregularity of the poem’s rhyme scheme and meter. The piece uses a rhyme scheme – AABCCBBDEEFFGGHHG – that switches once the rhyming pattern becomes expected, reintroduces rhymes from earlier in the poem, makes frequent use of near-rhymes, and at one point includes a line that rhymes with no other line in the poem, all of which coalesces so that they create an uncertain, confused tone within the poem. There is an equally offputting quality about the way that the sudden switches in meter occur – a line like “Municipal gum, it is dolorous” might be expected to be followed by a line of the same length and meter, but it is immediately succeeded by “To see you thus,” which is much shorter and uses a different meter – at the same time that it breaks a pattern, though, the poem rhymes, continuing to bolster a sense of uncomfortable continuity in the piece. Speech sounds also act as an extension of this poem’s tone, with guttural noises and consonance denoting negative elements in the poem – the section of the poem that compares the gumtree to an abused draft animal especially makes use of these techniques: Like that poor cart-horse / Castrated, broken, a thing wronged, / Strapped and buckled, its hell prolonged.” The ideal world, the “cool world of leafy forest halls,” on the other hand makes more use of assonance and uses softer and less contrasting consonants than appear in other parts of the poem. The use of sound in “Municipal Gum” seems to me like a good example of a poem conveying equal amount of emotion through form as through content, which, coupled with a physically short poem, makes this piece resonant without having to speak for long at all.

“Municipal Gum” deals with the out of place-ness of a gum tree in the middle of an urban environment, and that same dislocation in the poem’s speaker, who links themselves to the tree by calling the two of them “us” and addressing it as a “fellow citizen,” and that feeling is heightened significantly by the irregularity of the poem’s rhyme scheme and meter. The piece uses a rhyme scheme – AABCCBBDEEFFGGHHG – that switches once the rhyming pattern becomes expected, reintroduces rhymes from earlier in the poem, makes frequent use of near-rhymes, and at one point includes a line that rhymes with no other line in the poem, all of which coalesces so that they create an uncertain, confused tone within the poem. There is an equally offputting quality about the way that the sudden switches in meter occur – a line like “Municipal gum, it is dolorous” might be expected to be followed by a line of the same length and meter, but it is immediately succeeded by “To see you thus,” which is much shorter and uses a different meter – at the same time that it breaks a pattern, though, the poem rhymes, continuing to bolster a sense of uncomfortable continuity in the piece. Speech sounds also act as an extension of this poem’s tone, with guttural noises and consonance denoting negative elements in the poem – the section of the poem that compares the gumtree to an abused draft animal especially makes use of these techniques: Like that poor cart-horse / Castrated, broken, a thing wronged, / Strapped and buckled, its hell prolonged.” The ideal world, the “cool world of leafy forest halls,” on the other hand makes more use of assonance and uses softer and less contrasting consonants than appear in other parts of the poem. The use of sound in “Municipal Gum” seems to me like a good example of a poem conveying equal amount of emotion through form as through content, which, coupled with a physically short poem, makes this piece resonant without having to speak for long at all.