Hello, friends!

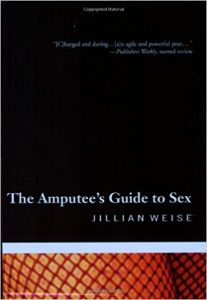

I’ve been reading books lately by poets with disabilities, specifically by poets who write about the human body and the human brain and why “norms” shouldn’t exist in such intricate and individualized systems. Disability studies and poetry lend themselves well to each other: the voice that poetry has is strong, even when a physical presence is overlooked or disregarded due to a disability. I would encourage you to check out the following poets who have disabilities, and read the brief NaRMo review that I wrote for Jillian Weise’s collection, “The Amputee’s Guide to Sex.”

Laurie is a poet born in Newport Beach, California. At seventeen years old, she was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. “I was diagnosed at the age of 17, so MS has defined much of my adult life. I consider what goes on in my body an important factor of who I am; we are inextricably linked, MS and me,” Lambeth shares. She often writes poems that reflect the individual body’s form within the context of the world. She has an MFA and PhD in creative writing from the University of Houston, and has been published in many high-profile reviews and journals. Her book “Veil and Burn” is highly regarded and coveted, as her poetry is very much involved with her disability and what it celebrates.

Arthur was an Australian lyric poet. He was born with cerebral palsy and was unable to speak clearly or write with a pen. Ultimately, he learned to type and overcame his physical disability enough to put pen to paper. He received a higher education and was wildly successful in the world of poetry and the arts. Banning valued compression and brevity in a poem, admiring the haiku especially. He named his disability “his own particular demon” but was able to produce phenomenal verses before his death in 1965.

Denise Leto is both a poet and a Senior Editor at the University of California, Berkeley. Her poems have been published in a multitude of journals and reviews. Leto’s latest poetry tells of the somatic experience of grief as allied to perceptions of disability. She has a form of vocal dyskinesia in which she cannot control the production of her voice, which infiltrates her work in notable ways.

“The Amputee’s Guide to Sex” by Jillian Weise is an electric and audacious collection of poetry that shows readers the complexity behind emotional and sexual intimacy when it comes to having a prosthetic leg. The poems are a dance set to (at times) hesitant music: the agile movement of sex with the unfriendly metal of a prosthetic seems incompatible to an unaware society.

However, to Weise, having a disability doesn’t keep a person from being a badass anywhere, including within the confines of the bedroom. Sardonic, thorny language litters the poems and adds an element of sarcasm, humor, and confidence to the collection, like this line in “Abscission”: “Your favorite post-coital pastime \ is nicknaming my scars.” However, poems like “Despite” show the micro aggressions that she faces even in moments of intimacy: “The leg would \ not slide on & would not \ slide on. He said he rather \ liked it, could \ kiss despite it. I know \ that word. It means \ the desire to hurt someone,” assaulting the reader with a delicate blow of irritation and pain.

As relationships become more intimate throughout the collection, so do the heartbreaks. “His hand felt the plastic of my leg \ and he froze. It was our first and last \ week. He called to say he wasn’t ready \ to date me…I thought he would make it. He had \ a dead father three years back. \ If that doesn’t show how entirely useless \ the body becomes, than what does?” reads the poem “Bust,” leaving the reader with the aching whisper of a question. The short, choppy line breaks and innovative images throughout the collection create a beautiful and enthralling world in which the arts and the human body are morphed, discovered, and uncovered deliciously.

*I have the book, currently on loan to Danielle, so feel free to borrow it whenever you’d like, or purchase one of your own here!

Happy reading 🙂