I’m surprised that in such a savvy course such as this, we’ve somehow totally circumvented the subject of zines. Zines are small, largely individually produced “magazines” (though many, if not most, tend to be smaller than that) that can address any topic under the sun. In fact, that’s the large appeal of zines: because they are so easy to send out and to physically produce (the actual creation process is, of course, a different story), fans of particular niche subjects can purchase zines regarding them relatively easily. And there’s also something to be said about interacting with zines that have nothing to do with something you’re interested in! I have a small collection of them, and one of my favorites is a small booklet of poetry all about how much the author hates John Green, putting the author in all of these distressing situations to explore misogyny and contempt. I don’t think I’ve touched a John Green book since I was thirteen; I certainly don’t have enough in me to hate the guy. But that doesn’t take away from the craft of the zine about him I own!

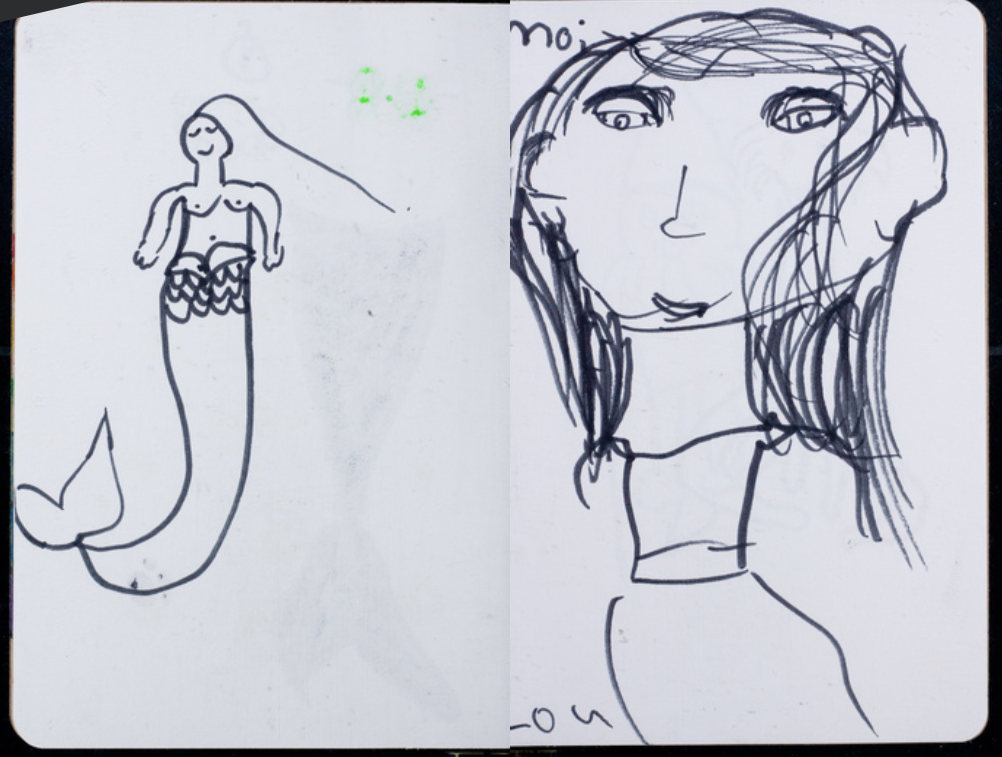

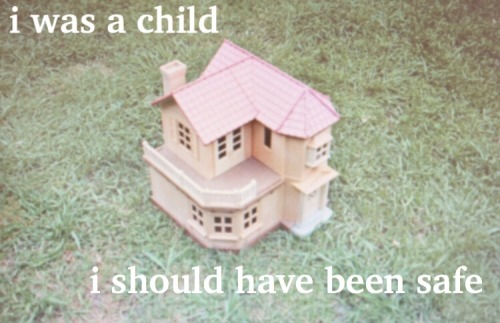

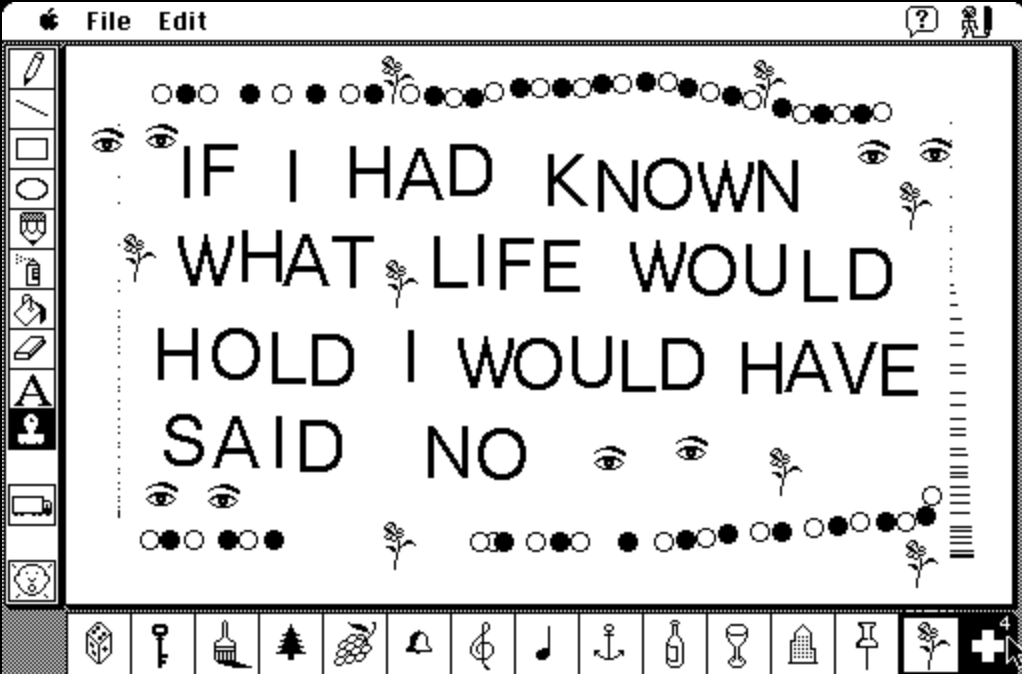

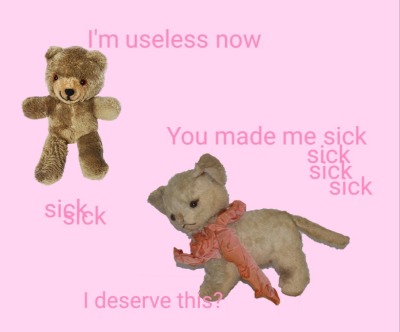

They look a little like this, if you’re wondering:

Looking up how to make them, physically speaking, will yield thousands of results, so I’m not going to go on much about printing and such. But I do want to bring up the fact that many zines, while made by a single (or handful) of people, can often take submissions from writers around the world. It’s a really low pressure, easy way to see some of your work in print; often when I am facing a writing block, I look up zines in search of submissions (I usually look on this independent publisher’s site for those; looks like the pickings are a bit slim this week!) and write according to what they are looking for. It’s a lot easier to submit to one than an actual literary magazine, and frankly, is more fun too. Many of them are looking for poetry or text submissions, and it’s fun to go out and find them!