I am most interested in three seemingly separate writing disciplines: the creative non fiction genre, the investigation and research put into journalism, and the unique form in poetry. So, when I read Erika Meitner’s creation of these things in “All that Blue Fire” and watched Katie get inspired as a result of it, I wanted to try it out myself. I plan on having this poem workshopped, so I won’t focus so much on how I wrote it and get you sick of the poem just yet. Instead, I’ll talk about how I gathered my information.

I am conducting a field study for my anthropology class, investigating the language of healing. The class discusses how language used in culture and context can assist a “sick person” in getting well again. For example, how does your doctor talk to you during checkups and how does this communication influence your healing process? Of course, western medicine is not the only nor necessarily the best way to “get well again”. There are many kinds of healing practices across different cultures, as there are many kinds of ways to be “sick”. I have chosen to focus on the practice of yoga and meditation, specifically at a studio here in Geneseo, NY.

So, for my research, I conducted an interview a few weeks back talking to one of the head instructors of the studio. I asked her a variety of questions, but there was a specific response I took a lot of interest in. I asked her how she first got into teaching yoga, and she told me that she started off by working with her professor in college, teaching meditation at a maximum security prison in the 1970s. She went on about her experiences and the reactions that the inmates had to meditation class. It was so cool to listen to!

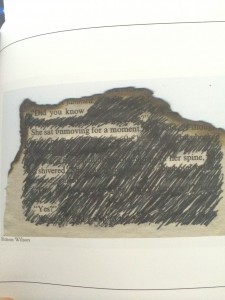

That story stuck in my head for a while, and when the idea of a journalistic-style poem was introduced to me, I automatically knew I should make a poem out of it. As I was listening to the interview recording, I noticed Angela (the instructor) mentioned “the riots of the early seventies”, and I wasn’t sure what she was specifically referring to. At the time, I shrugged it off as a reference to the counterculture, but now that I wanted to write a poem about it, I figured I’d be more specific. So I looked up Attica Correctional Facility, and read all about the Attica Prison Riot in 1971. Half of the prisoners, about a thousand people, upset with the mistreatment that went on in the prison, overthrew forty two members of the staff, and rather successfully. I knew so little about this historical event and was blown away by all of what Wikipedia had to tell me about it, I knew I had to write a second poem in the footnotes. Granted, a lot of the more detailed information doesn’t have citations, probably because the U.S. government wanted to protect themselves and didn’t release much information about the brutal retaliations by the guards. I encourage you to read up about it, and I hope you enjoy my poem I’ll be distributing on Thursday!